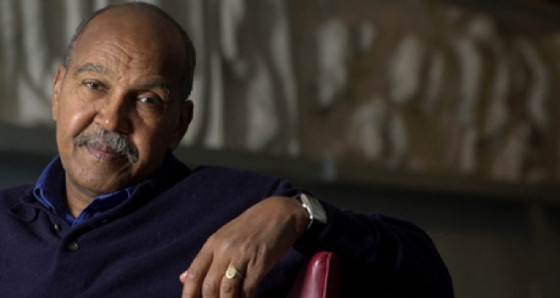

The current images of Somalia are those of a country ravaged by a 22-year dictatorship and perpetual civil war. Yet through 12 books and countless essays centered on Somalia, author Nuruddin Farah has refuted those images of his homeland and solidified his place as one of Africa’s leading literary voices. EBONY spoke with the global activist and educator on how he keeps Somalia alive through his writing.

The current images of Somalia are those of a country ravaged by a 22-year dictatorship and perpetual civil war. Yet through 12 books and countless essays centered on Somalia, author Nuruddin Farah has refuted those images of his homeland and solidified his place as one of Africa’s leading literary voices. EBONY spoke with the global activist and educator on how he keeps Somalia alive through his writing.

EBONY: Growing up in Somalia, books were not easily accessible. At what point did your interest in literature pique despite not having books at your fingertips?

Nuruddin Farah: Books for children specifically and books in general were not available. I had to read whatever books my older brother could lay his hands on. I was between 9 and 11 years old, and I had difficulties understanding many of the words. It was my brother’s idea to give me thick books, to decrease the amount of mischief I could get into.

EBONY: So early on you were introduced to authors and stories from around the world. How did that exposure influence you?

NF: I discovered that the Russians were writing about Russia and the French were writing about the French. So early on in my life I thought, wouldn’t it be necessary to write down stories in which Somali names—children’s names and parents’—would appear.

EBONY: Initially, it was impossible for you to tell your stories in Somalian. How did you move away from the oral tradition?

NF: In a way, tragically I could not [write] in Somali, my mother tongue. Somalia had no standardized script, so one could not write in Somalian.

I would be the first one to move away from [the oral tradition] but [not] completely. I go to the oral tradition quite often; it’s a treasure I borrow [from] and informs a great deal of the writing. I love the oral tradition, but I think one must transcend it, because the only person who can hear you is the person in front of you.

EBONY: How does the cosmopolitan Somalia you grew up in compare to present day Somalia?

NF: Things are terrible [with] the continued absence of the basic necessities in Somalia—in terms of education, in terms of health, in terms of peace, in terms of economic, in terms of everything. The Somali-speaking peninsula of the world is lacking far behind our brethren and sistren in the other neighboring countries.

The tragedy of Somalia is, they have been given a life of discontinuity for the past two decades, and that has affected them mentally, psychologically, educationally and socially.

EBONY: You were exiled for 22 years from Somalia under the regime of dictator Mohamed Siad Barre. Yet despite being forced out and living in numerous locations—India, South Africa, the United States—your writing primarily centers on Somali. What keeps that fire burning for you?

NF: Whenever I have written an article about other countries, people remind me I’m a Somalian. Even [though] Somalis don’t think I write in their view. They don’t like criticism [and] people telling them, “Look, you’re mucking up the situation, you can do better than this.”

My first novel, From a Crooked Rib, got me into trouble. They said, “Why are you telling the world that we treat our women badly?”

I was only 22, and the only thing I could see was that women were being treated quite badly. Therefore, I wrote about societal dictatorship—[where] within the society are the patriarchs and the matriarchs? A country makes [it] possible for a dictatorship to come rule the country. My argument is, if the people were a reconstructed people, tolerant of one another, willing to listen, more liberal in their views, we would not have suffered the tyranny of a dictator who ruled the country for [22] years.

EBONY: From Elba in From a Crooked Rib to Hiding in Plain Sight’s Bella, you write about women in charge of their own destinies. How do you respond to being called the “Somali feminist” in a region where it’s unheard of for a man to be a feminist?

NF: My intentions [are] to show that many Somali women are strong despite [a] society [that] pushes the women to the margin and disenfranchises women. Despite this, it’s thanks to the consistent hard work in Somali women that Somali society has continued to exist.

Somali men often engage in [clan] politics. “I am this and I am that and my clan family is that.” This doesn’t help society. Somali women are the ones who have kept the country, and its people survive the greatest odds. They held their heads high and worked very hard to make sure there was food on the table. Some of them had to endure the fact that they had to prostitute their bodies to be able for their families to survive.

I raise my hat to the women, and I say to the men, “damn you! You haven’t done anything.”

EBONY: You frequently bring up the topic of female genital mutilation. What causes you to speak out about it?

NF: When I wrote my first novel, [female genital mutilation] is described as barbaric and I never hesitated to call it barbaric. [It] describes a situation in which women are continually in danger, nearing close to death every time a woman gives birth to a child. The first question you always ask if a woman has given birth, “Has she survived?”

Now this is something that has less to do with Islamic religion and more to do with economics. The economics is that women are valueless if she is not virgin, and a woman who is not a virgin may not find a husband. Therefore she will remain a burden on the family.

Women would not want to go through the pain and suffering that they do first when this terrible thing is being done to them. Secondly, when they give birth or even when they’re having their menstrual period, they suffer because of that.

I was condemned for grazing the subject. They said, “It is none of your business you are a man.” Because I am a man and therefore I will marry one. One of them will be my sister. My future wife may be going through this. For that reason, I should speak about that barbaric thing.

EBONY: Your writing keeps the Somalia you once knew—and the current country ravaged by a dictatorship and continuing civil war—alive. What’s your inspiration?

NF: My books are a dialogue; a dialogue between society and myself. I don’t want everybody to agree with what I say, but I would like people to start thinking and using their heads. If I am wrong, please correct me. If I am right, please listen to my advice.

When I was born, a great many of my age group did not even survive beyond the age of 5. I usually say there probably was a reason why I have been spared: so that I could write books. That reason keeps me going. The world has been kind and welcomed me with open arms in many places, despite the occasional difficulties [as] an alien, an exile, a foreigner, a Black person, a Muslim. I say thank you to the world.

Daryeel Magazine

Daryeel Magazine